Hi all,

Today, in honor of World Diabetes Day, I wanted to share an essay about what it’s like to live with Type 1 diabetes, which I was diagnosed with in 2001, when I was 22 years old. I hope it might be useful to anyone out there who’s living with or caring for someone with the disease (as well as anyone who has a friend or loved one who has Type 1 and would like to better understand their experience) — it’s my attempt to explain the exhausting, scary, never-ending, life-threatening burden of essentially trying to be your own pancreas 24 hours a day, with a disease that doesn’t have a cure and that never gives you a break.

Before sharing the post, a note of personal gratitude for my own situation: not only was I born at a time when Type 1 was no longer a death sentence (which it was till 1923, when insulin was discovered), but I’m fortunate enough to have access to the most cutting edge diabetes treatments available (including a continuous glucose monitor, which I did not have when I wrote this essay). Most people are not so lucky. If you’d like to help, Life for a Child is an organization devoted to providing children around the world with insulin, diabetes supplies and diabetes education.

And if you know someone who has a first-degree relative with Type 1 diabetes, please encourage them to do a free screening test through TrialNet to see if they are at high risk of developing Type 1 diabetes within the next five years. Relatives of people with Type 1 are 15 times more likely than the general population to develop Type 1 diabetes. That’s bad. But the good news is that, for the first time in history, there is something you can do about it: teplizumab is a drug that’s been in development for decades but was just approved last year (here’s the FDA’s press release) that’s been shown to delay the onset of Type 1.

I was in a clinical trial for teplizumab back in 2001 and I cannot say enough good things about the experience — in fact, I wrote about for Popular Science here (and am happy to answer questions in the comments). And if you’ve been newly diagnosed or know anyone who has been, please encourage them to look into research studies to preserve some of their insulin-producing cells.

As for this essay itself, I wrote it in journalism school while I was in a science writing class taught by Michael Pollan, who had recently come out with The Omnivore’s Dilemma, and who inspired me and a bunch of my peers to pursue careers writing about food and science. He gave us 20 minutes or so during class to write a piece about our personal relationship with food, and this is what came out. I had no idea how much I’d been holding inside until I started writing it down.

Thanks for reading, everyone, and if you know anyone who might find this information or essay useful, I’d greatly appreciate it if you’d share it.

Catherine

Thinking About Diabetes with Every Bite

A version of this essay originally appeared in The New York Times in 2008

When I look at food, I don’t see food. I see sugar — in the form of carbohydrates — plotted on a multidimensional graph with proteins and fat and serving sizes and sickness and exercise and times of day.

I didn’t always do this. Before I received the diagnosis that I had Type 1 diabetes, I saw food as food, and ate it as such — simply, casually, with no real thought attached.

The winter of my senior year of college, after a bad cold and painful breakup, I began eating more — not to cope, but to feel full. I was hungry, always hungry. Hungry and thirsty and tired, piling my tray in the dining hall with pasta, cheese, dessert, getting up in the middle of the night to slurp water from my dorm’s bathroom faucet.

I gorged myself and yet my pants were looser, my arms thinner, my stomach flatter. One afternoon I threw it all up, convinced I had food poisoning. My stomach eventually settled, but my mind did not. The world swirled. I couldn’t stand without stumbling. On Feb. 17, 2001, I entered the hospital, and since that day, food has never been the same.

To live with Type 1 diabetes means to be aware, constantly aware, of insulin — a hormone produced in the pancreas that unlocks your cells so they can use the energy in your food, which circulates in your blood as glucose. A healthy person’s pancreas pumps out insulin in exact, perfect doses, masterfully managing the level of available glucose so that it never rises too high, which could lead to complications, or too low, which could kill you on the spot.

My pancreas, however, doesn’t make insulin. It can’t. For reasons no one can fully explain, my own immune system killed off the cells that produce it. That’s what Type 1 diabetes is — an autoimmune disease in which your body turns against itself. It’s frequently confused with the more prevalent form of diabetes, known as Type 2, but the diseases are not the same. Unlike Type 2 (which is challenging in its own ways), Type 1 diabetes can’t be prevented or managed with diet, exercise or oral medications. Instead, it requires artificial insulin — through injections, not pills — to stay alive. Before insulin was discovered in 1922, Type 1 diabetes was a terminal disease.

Today, artificial insulin means that a Type 1 diagnosis is not a death sentence. But living with diabetes takes much more than simply giving yourself shots. It requires constant, unwavering attention to your meals, lifestyle and medication — and even the most conscientious person with diabetes will never achieve the balance that a healthy pancreas effortlessly maintains. If I take too much insulin, my blood sugar will drop too low; my body will sweat and tremble; I will become anxious, irritable and confused. If I don’t quickly eat something to give my body the glucose it needs — or, worse, if it’s the middle of the night and I am too deeply asleep to notice the warnings — I could lapse into seizures and unconsciousness and never wake up.

It would be easier to keep my blood sugar a little too high, to coast comfortably above the turbulence of tight control. But doing so would mean ignoring the destruction caused by high sugar levels — slower than a seizure, but devastating nonetheless: the capillaries in my eyes bursting from too much glucose, the tiny vessels in my kidneys overwhelmed by sweetness, the nerves in my feet losing their ability to feel.

Instead I calculate constantly, measuring my food’s potential effect on my blood against my desire to eat it, trying to walk a Goldilocks tightrope where my sugar is not too low, but also not too high. My blood sugar’s reaction to food depends on far more than the food itself. If I exercise before or after eating, it is different. If it’s the morning, it is different. If I have my period, it is different. If I am tired or stressed or sick, it is different.

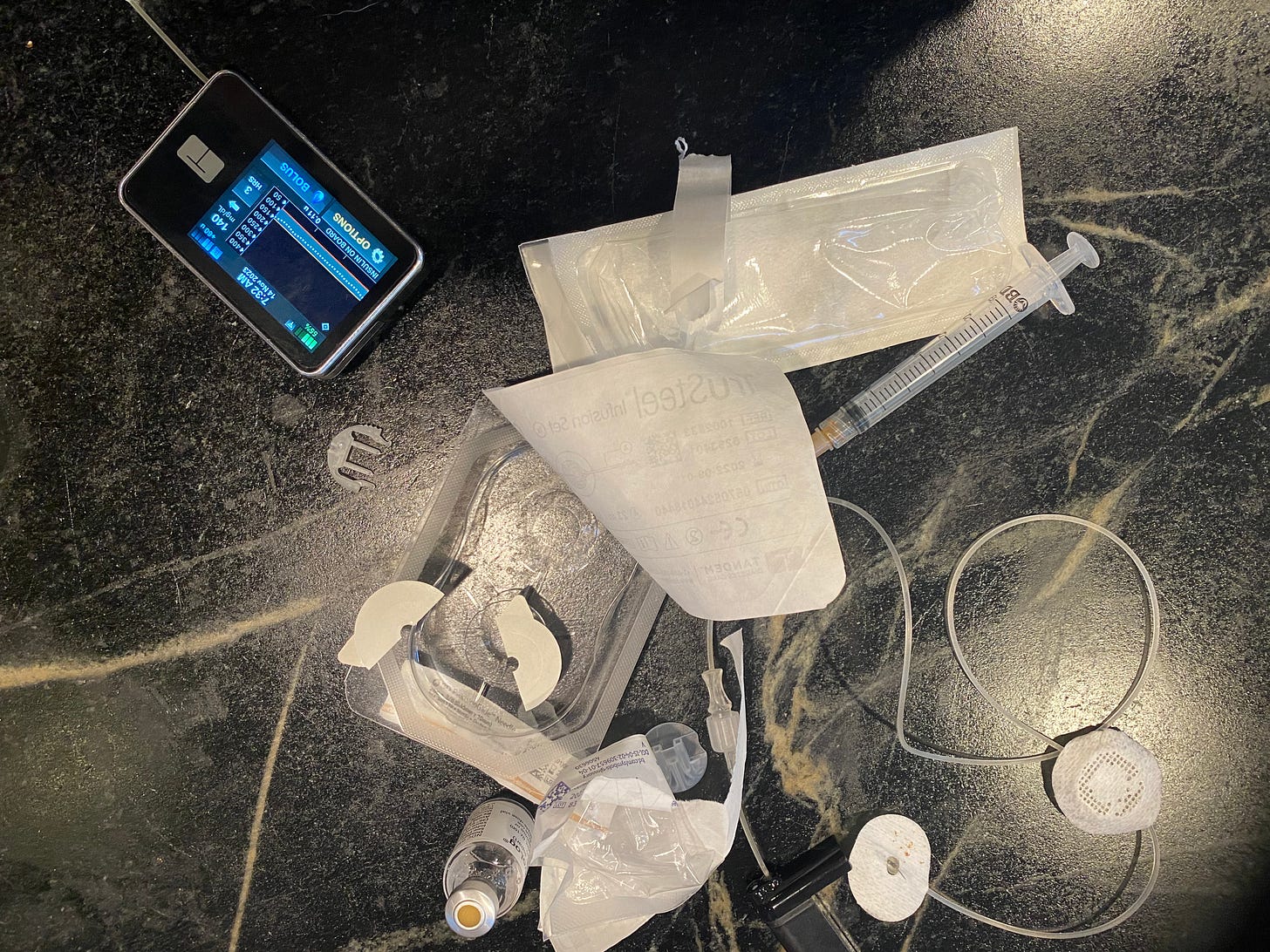

From the outside, diabetes is invisible. Look closer, though, and my fingertips are calloused where I prick them to test my blood sugar 10, 12 times a day. A bulge in my pocket reveals my insulin pump, a machine connected to me by a tube that, in giving me insulin, keeps me alive; scars from its insertion sites pepper my hips. My pump means fewer injections, but it has no brain — I still decide how much insulin to take. Instead, it is a literal tether, its plastic stint in my side a reminder, as I sleep with it, exercise with it, and go to dinner with it tucked in my bra, that I have a disease, that there is something wrong. Diabetes’s subtlety is both a blessing and a curse, saving me from stares and pity but keeping the difficulty of the disease — and its severity — hidden as well.

I hate it, diabetes — wish I could take a vacation from it, eat a slice of bread without calculating carbohydrates or have dinner with friends without fear. But I can’t. So instead I try to flip things around, to use the challenges of diabetes as an inspiration to live as fully as I would if I didn’t have it — if not more so.

One of the best decisions I ever made was to participate in a clinical study for a new experimental drug as soon as I learned my diagnosis; I encourage everyone to do the same. As my endocrinologist, who himself has Type 1 diabetes, explained to me, “We need just about every single newly diagnosed person to get involved in a trial. It’s the only way things won’t be the same in five years.” You can find a clinical trial for Type 1 through Trial Net, the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the Immune Tolerance Network or ClinicalTrials.gov.

Living with Type 1 is an exercise in measurements and judgments and willpower and constant self-restraint. For me, the most difficult part is accepting that I will never be perfect; I will always have bad days and, perhaps worse, there is no way for me to “win.” Like everyone with Type 1 diabetes, I will have to keep at it — every day, every hour, until we finally figure out a cure.

The best I can do in the meantime is to control my disease without allowing it to control me, and to not let the autoimmune attack on my pancreas develop into an emotional attack on myself.

And, of course, to dream of a day when I can once again think of food as food — simple, enjoyable, with no strings attached.

Leftovers from this morning’s insulin pump change.

I was diagnosed at 17. Fifty three years ago. I wrote this poem for the newly diagnosed:

Write darling.

Write

Every

Fucking

Detail

of your agony.

Carve

your losses

into the page.

Soak them

with the tears

of your

disappointment.

You

are worth

all

the time

it takes

to get well.

Step back.

Witness

it all

from a distance.

Put away the

number two pencil.

This is not

a test,

but

An invitation

to love yourself

more,

an invitation

to give

sweetness

access

to your pain.

An invitation

to learn

the subtle,

but

life-changing

difference

between

checking up

and

checking in.

Study

The great for givers.

Ask

for the recipe

of their balm.

You will need it

when you break

your own

heart.

And you will break it.

But less and less

as you receive and

give mercy

to yourself.

Do your best

not to use

your illness

as an excuse

or currency.

Excuses are kryptonite.

Dare to step into your power.

Healers if all

sizes and shapes

will arrive

at your door.

Some

will be

the real deal.

Some,

snake oil

salesmen.

Invite them in.

They are

reflections

of you.

Fortune tellers

will predict

Blindness.

Stroke.

Amputation.

Unbutton you blouse

and gaze

into your the heart

of your own

crystal ball.

Linger there.

Faking optimism

is a form

Of self-abandonment.

Dismissing it

altogether

is abuse.

Mistakes will happen.

Overdoses will happen.

An overdosed mind

is a mind

without sugar.

A mind

unable

to think

the old

thoughts.

Mistakes

have the power

to usher in

new worlds.

Allow all

The banished

parts of you

a seat

at your table.

Gather the sweetness

that needs

no measurement,

requires

no injection

and pour it

generously

over

every

frightened

part

of

you.

Breathe, darling.

And again now.

Breathe.

Sorry to hear that.

Diabetes in general is indeed a very widespread and life-changing medical condition.

Thanks for sharing.