Grab Bag: A Chicken in Every Plot, a Coop in Every Backyard

Backyard chickens and the people who love them

Every once in a while I resuscitate an article I wrote as a freelancer, and republish it under the Grab Bag section of my Substack. (If this section had a tagline, it would be “Stick your hand in and see what you get!”—except that sounds vaguely ominous/obscene, so I’m just going to leave it as Grab Bag, and suggest that you ignore this parenthetical.) Anyway, this article is about people who keep chickens in their backyard. Years later, during the early days of the pandemic, this article inspired me to rent chickens myself (yes, I said rent), an adventure that perhaps I’ll write about some day. Anyway, this piece appeared in The New York Times in 2007. Enjoy!

NOVELLA CARPENTER remembers the day she killed her first chicken.

It was a rooster named Twitchy who had been injured by an opossum that got into her backyard chicken flock. About to leave for vacation, Ms. Carpenter, 34, had no way of caring for the wounded Twitchy while she was away. So she took it to the back porch and chopped off its head.

“I cried,” she said. “I buried it. It was very sad. But then I realized that I could do it again and eat it.”

The next time she thinned her flock, she and her boyfriend invited friends and made rooster burgers flavored with oregano, marjoram and rosemary from the garden.

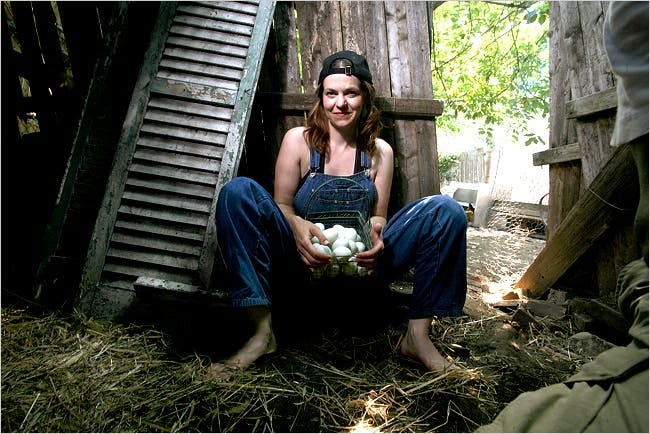

Raising chickens for meat or eggs may not be unusual in farm country. But Ms. Carpenter, a writer, does not live on a farm. She and her boyfriend rent an apartment a block from Interstate 980 in Oakland, Calif., next to an abandoned lot that they have appropriated as a garden.

City dwellers who raise chickens are springing up around the country. Groups organized on the Internet in Los Angeles, Phoenix and Austin, Tex., are host to chicken-centric social events, and there are dozens of books — a whole new form of chick lit — on raising chickens, including Barbara Kilarski’s “Keep Chickens! Tending Small Flocks in Cities, Suburbs and Other Small Spaces,” and related titles like “Anyone Can Build a Tub-Style Mechanical Chicken Plucker,” by Herrick Kimball.

Backyard Poultry, a magazine founded in 2006, caters to the urban segment of its audience with articles like “Chickens in the City.” Two magazines with a broader readership, New York and The New Yorker, recently published articles by writers whose attempts to eat an all-local diet involved city-bred birds.

On the Internet, thecitychicken.com offers tips to urban owners on how to keep chickens on a high-rise terrace and what to do if your chickens try to attack you. (“I’m afraid to go into my backyard,” one reader wrote. “Have you ever heard of this?”) And hundreds of chicken fans visit backyardchickens.com, where owners brag about egg size and discuss their Wyandottes, Silkies and Rhode Island Reds.

Because they straddle the line between livestock and pets, chickens are allowed in some unexpected places. New York City, Oakland, San Francisco, Houston, Chicago, Seattle and Portland, Ore., are chicken-friendly. When restrictions exist, they usually affect roosters, which are sometimes used for cockfighting and whose crowing can wake up the neighborhood.

That isn’t to say that urban chicken owners never have to put up a fight. Backyard chickens were not allowed in Madison, Wis., until 2005, when a group calling itself the poultry underground persuaded the city to change its rules. (The group now runs a Web site called madcitychickens.com.) In 2004 a member of the Oakland, Calif., City Council attempted to ban roosters and limit city hens to two per household, but an enthusiastic group of “crazy chicken ladies” showed up, said Maureen Forys, 35, a chicken owner who attended the council meeting. As a result, roosters are forbidden but there is no limit on hens.

Clandestine coops turn up even in cities like Boston, where they are banned outright. “We catch them all the time,” said a representative from Boston’s animal control unit, who asked to remain anonymous because he was not authorized to speak to the news media about poultry. “There’s chickens all over the place.”

For some of these farmers, poultry is just the beginning. “Chickens are the gateway animal for urban farming,” said Ms. Carpenter, who is writing a book about her menagerie, which consists of 20 chickens, 14 rabbits, 4 turkeys, a duck, and, until a week ago, 2 pigs. (Recently slaughtered, the pigs now reside in her freezers.)

The motivations of urban chicken farmers vary. Willow Rosenthal, 35, who runs City Slicker Farms in West Oakland, Calif., and helps low-income families raise chickens as a source of sustainable, healthy food, sees them as a route to better nutrition. On the other hand, Ms. Forys sees owning chickens as a way to reconnect with where her meals come from.

“Over the past two generations we’ve become completely separated from our food,” she said. “There’s something really wrong with that.”

David Morris, 60, a bakery owner who raises 27 birds in his backyard in Berkeley, Calif., got his first chickens in 1978 so he could recycle bread crumbs from his bakery; today he sells excess eggs to neighbors and employees, and slaughters his unproductive hens for food. His flock rewards him with fertilizer: each chicken can produce 50 pounds of dry waste a year. “I like to say that everything in my garden is chicken-related,” he said.

For people like Mr. Morris and Ms. Carpenter, an advantage of raising chickens is their meat. The older a chicken is and the more exercise it gets, the more flavor and texture it will have. Since most factory chickens are confined in small cages and killed when they are about 6 weeks old, their flavor is weaker than their backyard-raised peers, who may be 2 or 3 years old before they make it to the dinner table.

(Of course, chickens are not like wine: age does not mean quality. Older birds may have more flavor, but they can be gamier, with tough, stringy meat.)

“You don’t realize how bland modern chicken flavor is, even if it’s organic, unless you eat a home-raised one that wasn’t slaughtered at a young age,” Mr. Morris said.

The most common culinary reason people keep chickens in the city, though, is their eggs. Depending on the hens’ diets, eggs from home-raised chickens can have stronger shells, brighter, richer yolks and higher levels of nutrients like omega-3 fatty acids than their commercially-raised counterparts.

They are also fresher. Whereas an egg from a backyard chicken can be in the pan in minutes, a commercial egg can take two or three days to go from its production facility to a distributor, said Linda Braun, consumer services director for the American Egg Board. It can then sit in a warehouse for as long as a week before being delivered to a store.

Age affects how well an egg’s white and yolk hold together (the fresher the egg, the thicker they will be). As for taste, chicken owners disagree about how much home-raised eggs differ from those bought at the store.

“People say they taste better,” said Jessica Gruner, who has two chickens in her yard in Berkeley. “I think they taste like eggs. They’re prettier, but they’re just eggs.”

Julie Plasencia, a freelance photographer who keeps four chickens in a bamboo grove outside her house in Oakland, disagreed. “When you crack them open the yolk is almost orange it’s so fresh,” she said. “And it stands up. It doesn’t go flat. We eat them soft-boiled and they’re just really, really rich. The yolk part is very creamy and the outside part has a very nice fresh flavor.”

People who raise chickens just for eggs are likely to develop personal relationships with their birds, giving them names (often based on literary characters) and treating them like slightly messy pets. Chicken eaters, on the other hand, tend not to name the members of their flocks.

One notable exception is LeNell Smothers, 36, a liquor store owner in Red Hook, Brooklyn. She keeps six hens in her backyard and drops their eggs (whites, yolks or both) into cocktails like whiskey sours; Mae Wests; Ramos gin fizzes; and a drink a friend invented called the Good Humor — a blend of cream, egg yolk and the Italian aperitif Aperol. Unlike most chicken farmers, Ms. Smothers names her hens after family members. (“I’ll probably slaughter them myself,” she said.)

But there’s a simpler reason to keep chickens than for their taste, their sustainability or for caring about how they have been treated. “I could go to the grocery store and buy eggs from happy chickens,” said Reilly O’Neal, 32, whose San Francisco flock consists of two Golden Sex-link pullets and a Barred Rock named Zorah. “But this is so much more fun.”

This article appeared in The New York Times in 2007.